Sweetheart of the Rodeo is the sixth album by rock band the Byrds… officially. The Byrds are a group that tests the limits of what a band is and how it’s defined. If you follow membership as detailing what a band “is”, specifically by a mostly consistent lineup, then the Byrds definitely fail to remain the same throughout. However, when they lose their Byrd credibility is open to debate. The first lineup of the group was Gene Clark, Roger McGuinn, and David Crosby; all guitarists and singers. Originally they recorded under a different name, the Beefeaters. You could argue that bassist Chris Hillman is an original member of the Byrds due to only missing out being in the band on the Beefeaters single, but in fact he’s not on the first single credited to the Byrds either, the famous “Mr. Tambourine Man”. Hillman and drummer Michael Clarke were indeed members at that point, but did not play on the record. For the first two albums, clearly the central characters of the group were McGuinn and Clark. They were the primary singers and songwriters. No other Byrd got a songwriting credit on those first two LPs. This seemingly only changed because in early 1966 Gene Clark left the outfit.

Considering that Clark was the main songwriter, you could claim that the Byrds end here, in their place a new slightly different group, but the band can generally be given a pass due to still having four essentially original members. The third album by the band, Fifth Dimension, has six compositions from David Crosby (who the others didn’t really like), though three of those were written by all four members. Crosby’s fortunes would soon change. The fourth LP Younger Than Yesterday saw Hillman, who had never before had a song he wrote solo make an album, now gets four out of eleven tracks all to himself. Crosby only fairs a little worse. McGuinn gets less than either, so now neither of the original prominent songwriters are still very central. Shortly into sessions for the fifth album The Notorious Byrd Brothers, Clarke quit and shortly after Crosby’s fired. Gene Clark of all people was brought into the fold once again, but he would be gone in a flash. At most, he managed two backing vocals and one co-credit for writing. The album’s sessions would continue with just McGuinn and Hillman before Clarke rejoined and would too only serve a very brief second tenure, still never really being a songwriter. It is funny that of these five albums, all except the fourth feature all five members, but they also feel so distinct in their own ways. The first band heads were Clark, Crosby, and McGuinn, which changed to Clark and McGuinn, then McGuinn, Crosby, and Hillman, then McGuinn took a backseat for a hot second, and eventually McGuinn and Hillman. Even if you are to claim that all of this is constant enough to constitute the same band, then stylistic and personnel differences are about to stretch credulity to breaking point.

The reason why the group’s number six is loved or hated is because of the Floridian invasion of the Californian Byrds, Gram Parsons. Determined to popularize what is simply called “country rock” or “progressive country”, but he called “Cosmic American Music”, Parsons created a variety of bands and debatably his first classic album with the International Submarine Band called Safe At Home. That album was recorded in 1967, at basically the same time as Byrd Brothers. Parsons’ plan was to popularize his genre and the opportunity came when he met Hillman. Hillman would prove to be a mostly consistent ally of Parson and he was invited in the band after the Crosby-shaped vacancy. Clearly McGuinn was showing some level of interest in country, due to wanting the next album to cover the history of American popular music, featuring bluegrass, country, jazz, rhythm and blues, rock, and finally electronic. Perhaps this is why Parsons showed interest in the Byrds and the Byrds in him? While there are certainly nuances that are not included in the history books, the story goes that in order to get his way, Parsons claimed that country fans would flock to the music if they turned full country and got Hillman excited in the prospect. Parsons’ imposing would not stop, as he managed to record six lead vocals of the eleven songs on the album. He only wrote two songs, but the other members provided zero. While the Byrds did in fact record a lot of covers, this marks a turning point considering that at best you only get two songs written by a Byrd. However, at the time Parsons was not signed as an official member of the band, which has often been called a “hired gun”. Even if you say he is an official member, in the informal annals of history he’s not been counted. It’s like saying Pete Best is one of the Beatles. Sure, he was a member for a brief point, but he isn’t included in the cultural perception and main canon of music. Thus, in an informal sense, we only have two Byrds here. This would not be the first or last record to feature two Byrds, but in other cases the album isn’t credited as such.

While the Byrds’ original material sometimes leans on the syrupy side of folk rock, Parsons adds a sense of edge in the removal of 60s-pop riffs and inclusion of warm and romantic vocals, among many other factors. He seemed to care more for the impression he’s making on record rather than live, seeing as he was sometimes very flakey. At one point he refused to do a tour, suspected to be because he wanted to hangout with the Rolling Stones. Thus, the country image of the Byrds would be more minimal. Yet on record, he even transforms common Byrds tropes. A signature of their albums are covers of Bob Dylan songs. The two chosen for this album, opener “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere” and closer “Nothing Was Delivered”, feature the band’s signature vocal of Roger McGuinn and the group harmonizing, but now those harmonies are moved to the foreground. To contrast with a track like “Mr. Tambourine Man”, the background singers only seem to be enhancing the lead. Now, they stand up at the front for the chorus. The lead track also starts with a decidedly un-rocking and moody country riff, setting the tone perfectly. The use of an organ by Gram Parsons and pedal steel by Lloyd Green also create distinctions. Note that neither of those instruments are on “Mr. Tambourine Man”. What is on that original single is a piano, and what McGuinn was looking for after firing David Crosby was a jazz pianist. Gram has instead used an instrument more common in country music. Amusingly, in Parsons’ next band, he would cover a Dylan song, possibly being inspired by the Byrds!

Despite both Dylan songs being written recently at the time of recording, there are several much older songs that inspired some members. One notable example is the Louvin Brothers’ “The Christian Life”, which features the sorts of subject matter that the Byrds’ audience, and the Byrds themselves, would probably not subscribe to. It’s an admonishment of sinful behavior and celebrates living a virtuous lifestyle, yet Gram Parsons was a person who partook in partying and drugs. This even applies to one of the song’s writers, Ira Louvin, who died young from his alcoholism. Regardless, the unpretentious and passionate performances of the Louvins clearly had an effect on Parsons. By extension, many of the tracks on the record present deal with seedy behavior and even full on criminality, while featuring some sort of virtuous quality, such as an affinity for Christianity. “You’re Still On My Mind” covers a man who drinks his problems away, who is especially humanized with lines like, “Alone and forsaken, so blue I could cry.” “One Hundred Years From Now” suggests a societal failure to escape from judgmental and destructive behavior.

The fiddle solo on “I Am A Pilgrim” is a favorite element, being an early statement not to expect straight rock and roll. Hillman’s singing makes for a sobering contrast to the much rougher voice of Parsons. McGuinn’s voice works well on certain tracks, but his comparative lack of interest in this music shows. On “The Christian Life”, he has a southern drawl that sounds fake and overly stressed. This overemphasis can similarly be heard on “You Don’t Miss Your Water”. Despite being written by Parsons, “One Hundred Years From Now” also feels very Byrd-y, mainly in its vocals, strangely performed by McGuinn and Hillman. This is mainly in the harmonies’ folk style. The socially conscious and subtle lyrics are by contrast more forward thinking and representative of Gram and his Americana heroes. The song could be interpreted as addressing opponents of the Civil Rights movement, asking how they’ll be perceived in the future. These three mentioned McGuinn-sung songs were infamously previously recorded by Parsons and then replaced. Parsons’ versions are much more soulful and effortful. While the best version possible of this record would include those Parsons efforts, it is understandable why they were replaced. This is labeled a Byrds album and if Gram got six vocals on the LP, it would barely even be identifiable as the same band.

A personal favorite track is “Pretty Boy Floyd”. Epitomizing many themes of the album, the protagonist is an outlaw who despite killing someone, receives a sympathetic portrayal. It respects the Woody Guthrie original in its celebration of those that are apparently unfairly treated by the government. The opening lyrics being someone saying they are telling a story with a clean vocal suggests that this song and tale are a piece of history that should be repeated, even to the audience. “Well gather round me children, a story I will tell.” The track opens with a banjo to get in the mood and includes many instruments you wouldn’t see in straight rock and roll, like a mandolin. Chris Hillman’s first instrument he got serious with was a mandolin. The two recorded bands Hillman was in prior to the Byrds feature him on the instrument. The acoustic symphony stands opposed to the electric guitars more prominent in the band’s earlier work. Note the brief solos which are dominated by the banjo, with a fiddle and double bass to the side backing it.

While Guthrie is not a conventional singer, his layman vocal qualities usually work to the advantage of how he writes his song. He includes the coldness of the worlds he details. McGuinn by comparison sings this, and other songs, with a more positive attitude. This works to good effect where he can be sarcastic, on tracks like the opener; “Strap yourself to a tree with roots. You ain’t goin’ nowhere.” He lacks the morbidity that should be present for a line like, “As through this life you travel, you meet some funny men. Some rob you with a six-gun, and some with a fountain pen.” Regardless, McGuinn’s style is solid due to how pretty its melody is and having a storyteller tone. Maybe he is a storyteller that looks more on the bright side? Even when faced with a lyric like, “Every crime in Oklahoma was added to his name.” This version of the song is also much jauntier than with Guthrie. You’d think this song would be sung or chosen by Parsons, who has a closer voice, but in fact it seems to have really been McGuinn. It makes sense considering Guthrie was more of a folky and inspired the 60s protest music movement. Despite such material not seeing release until after his death, Parsons also recorded many folk numbers during that time.

Especially jaunty is Gram Parsons’ first vocal on the album, “You’re Still On My Mind”. The drums, by briefly official Byrd Kevin Kelley, are more prominent and the guitar more driving. The danceable grooves make this about the closest we get to a rock song, despite the flavors consistent with this record, such as the lack of an electric guitar. While a fine track, it is not as revolutionary as some other works here, in terms of the playing and singing. You would expect Gram to have a more soulful style or the instruments to reflect more influences. That style is used to great effect on the haunting “Life In Prison”. Inspired by singer-songwriter Merle Haggard, Parsons turns in an impassioned portrait of a man just wishing to die instead of wasting away in a cell. His vocal is only mildly more restrained than a plea, with a sense of pain and sadness constantly prevalent. The guitar is especially stabbing, like reflecting the feelings of the singer. The playing feels very surrounding, possibly inspired by Phil Spector’s wall of sound. The effect is to show this story and singer as a piece of history, just like everyone else depicted. It also nicely sets up the ending of the record.

One particularly powerful lyric in the Haggard original is, “Insane with rage, I took my darling’s life, because I loved her more than life. My dream for her will last a long long time.” This was changed to, “With trembling hands, I killed my darlin’ wife, because I loved her more than life. My love for her will last a long, long time.” The original implies that the act was done in a crime of passion that may have only lasted a moment, while the cover implies quivering and angst, as if this is something the singer is more conscious of. Seeing as he talks about finding life to just be causing him suffering, saying “I prayed they’d sentence me to die, but they wanted me to live and I know why”, there is the implication that he’s always wanted to die and may have desired to have his wife with him in death? While the subject matter is horrific, you can’t deny the themes of the album, humanizing social outcasts and giving a glimpse into what they’re like. Such themes can be found in various country songs, like Haggard’s. The song amplifies the subtle tension and unsettling qualities seen throughout, like on “Blue Canadian Rockies”.

OVERVIEW

Despite the fresh and new sound for the time, it is important to note that this is a rock record, as well as country. You still get a lot of verse-chorus-verse structures and I-IV-V blues chords, even if on not every track. The “talking blues” style that someone like Woody Guthrie employed is not used in a traditional sense. “Pretty Boy Floyd” is an example of this, but here it is very much sung instead of something closer to just talking, as Guthrie employed. Despite the minimization of commercial qualities, they are still there, notably in the use of popular Dylan songs, even if their arrangements are not faithful to Dylan’s. Amusingly on “the Basement Tapes” versions of these songs that the Byrds probably heard, Dylan uses a Guthrie-esque talk-singing style.

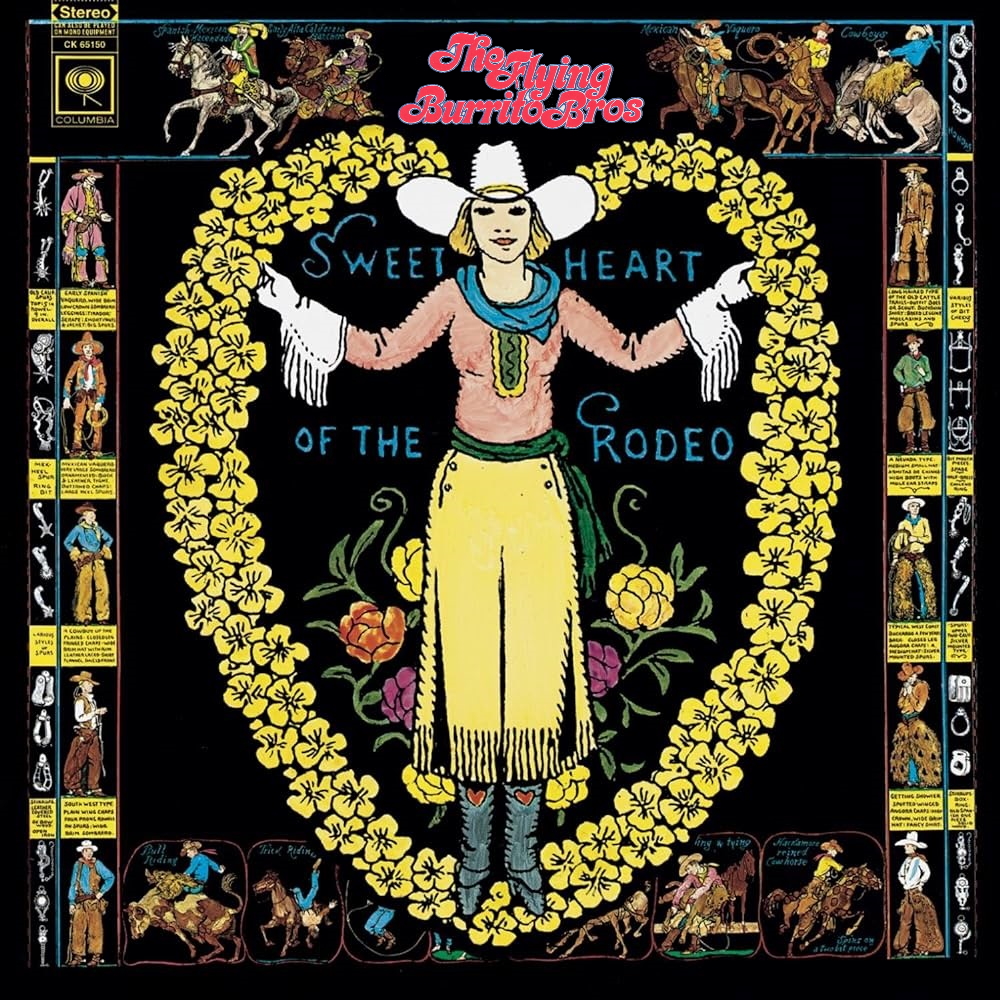

While the Byrds were never miles from country, especially folk which they utilized, arguably being country or country-adjacent; they never would have made something like this album without the leading hand of Gram Parsons, someone who also would never have lasted long with them no matter what. Note that David Crosby’s egomaniacal behavior did him no favors. Considering that stylistically this is not a Byrds album, what is it? Gram Parsons himself wanted it to be credited to “Gram Parsons & The Byrds”, showing the creative force here desired such a distinction. Regardless, he clearly didn’t identify strongly with the band, as he’d later say. I’m also surprised he bothered asking for that considering there was no way that would be allowed. He wasn’t even a famous name at the time, but he’s acting like a head honcho! After Parsons was fired by the Byrds, the sound of this album would later be continued by Gram’s next band, The Flying Burrito Brothers. Chris Hillman, despite issues with him, would join Parsons, leaving the Byrds as well. The Burritos continue where this record left off with more blending of different genres, including more prominent rock conventions. The pedal steel and mandolin would become mainstays of the band. For the record, I subscribe to the typical belief that any Burrito business after Gram left doesn’t count and isn’t the same thing. He and Chris were the only prominent songwriters before the former left, so without him it’s a different beast. Thus, Sweetheart is a Flying Burrito Brothers album. The only kink in this armor is that unfortunately the only other Burrito constant during the Parsons-era, “Sneaky” Pete Kleinow, is not on the “Byrds” outfit, but he wasn’t much of a creative force anyway. His inclusion would have still been appreciated.

After Chris Hillman left the Byrds, Roger McGuinn was not to be discouraged and continued onward. The seventh Byrds album, Dr. Byrds & Mr. Hyde, would have no members of any previous Byrds lineup other than McGuinn. As such, many say a name change was in order. Even with the Burritos, of the four albums that feature Hillman, three also feature none other than Michael Clarke. (Don’t even get me started on the many lineups of this band.) They had more Byrds than the actual late in the day Byrds. This gets even more confusing considering in the time frame of the late 60s-early 70s, various Byrds appeared on Gene Clark solo albums. Eventually Clark, McGuinn, and Hillman would team up, not even able to call themselves the Byrds despite having more true members than in 1968, without being interrupted by an outsider.

Regardless of who made the music or what it’s called, you can’t argue that Sweetheart of the Rodeo is a seminal work. It is unfortunately hampered by some avenues, like in its attempt to either stick to a past arrangement or improve it and fail. Not that this is a “fault”, but it’s also not the first country rock album. Ignoring Safe At Home, Michael Nesmith and even Gene Clark arguably beat Gram to the punch. Going back to the 50s, you can hear what is essentially a similar blend in the music of the Louvin Brothers and others. Regardless, this ode to the old and new of American popular music is as varied as it is unified, by outlaws and criminals and women. The depiction of a woman on the cover feels like the perfect embodiment of what drives creation and passion. You see themes from the environmentalist movement, like in “Hickory Wind”, where Parsons wants to be away from commercialized society. You see themes of unfair prejudice, as is implied in “Pretty Boy Floyd”. As was McGuinn’s intention, there are themes of many genres of popular music, like soul on “You Don’t Miss Your Water”, though most that aren’t country are more muted. Even Gram embodies the rebellious spirit of being almost a nobody that schemed his way up the ranks to be a revolutionary, who burned short but very, very bright; just like Floyd. It’s hard to go wrong with it… especially if you sub back in the Parsons-sung versions of songs McGuinn recorded over.